Dissertation Research

Do out-of-district donors distort representation between members and their constituents?

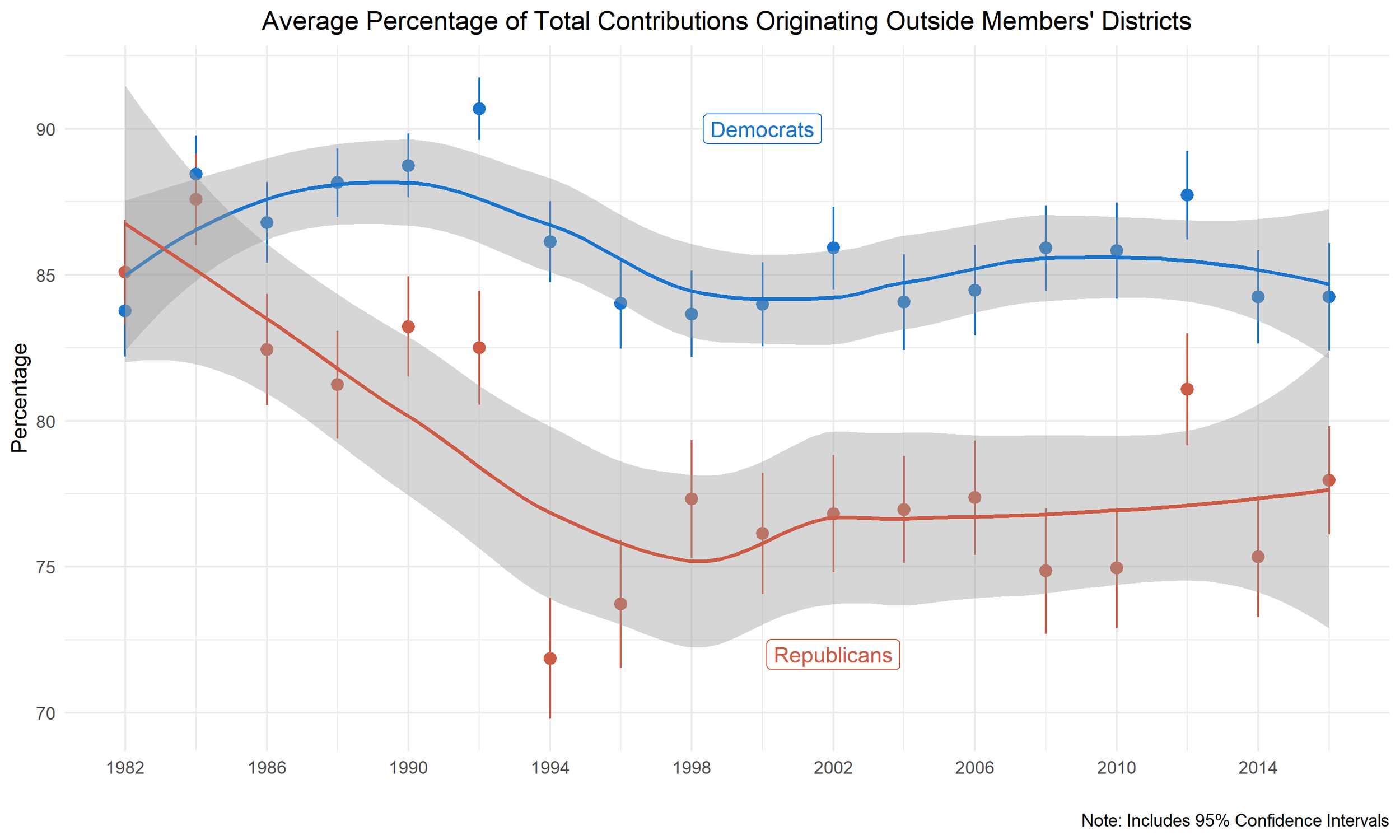

Three statistics motivate my primary research agenda. First, Open Secrets reports that congressional campaigns raised 8.7 billion dollars in the 2020 election – the most in American history. Further, between 2008 and 2020, the amount of money raised by campaigns increased by almost 200 percent. Lastly, 8 out of every 10 dollars that members of Congress receive originates from outside their congressional district. Together, these statistics suggest that members of Congress rely on out-of-district donors (not their constituents) to meet the rising cost of political campaigns. My primary research agenda explores the consequences.

I argue that members’ reelection fortunes are no longer dictated solely (or even primarily) by their territorial constituency. Instead, members appeal to a donor constituency composed of a broad network of out-of-district donors – the main financiers of congressional campaigns. In signaling these donors, I find evidence that out-of-district contributors distort representation between members and their constituents.

To assess out-of-district contributors’ influence on congressional representation, I leverage redistricting as an identification strategy. I argue that redistricting represents an as-if random reshuffling of donors and districts. As a result, redistricting breaks fundraising and representational ties, making it a useful tool for researchers aiming to understand how money influences representatives’ behavior without concerns about reverse causation. Operationally, I record the number of in-district donors redistricting displaces across each incumbents’ congressional district an exogenous independent variable and I use Bonica’s (2014) ideological scores to measure members’ responsiveness to their constituents and out-of-distinct donors.

I find that redistricting leads to greater reliance on out-of-district donations and better representation for out-of-district donors relative to constituents, which suggests that constituents experience agency loss. Normativity, my results raise essential concerns about the role of money in politics and the quality of democratic representation.

Relative to the past literature, my research examines the influence of out-of-district donors across 18 election cycles -- the largest number of election cycles examined by any study. I use redistricting as an identification strategy by leveraging the exogenous change to members’ districts. I advance Crespin and Edward’s (2016) measure of district change by using donors instead of citizens, which works better in the context of Campaign Finance. I use CFscores to estimate the ideology of members’ actual out-of-district donors, as opposed to merely the ideology of the national donor base. My theoretical contribution examines the competing pressures members face from their constituency and out-of-district donors, thereby, extending Mansbridge’s “monetary surrogacy” theory and turning our traditional concept of representation on its head.